Zen: History and Tradition

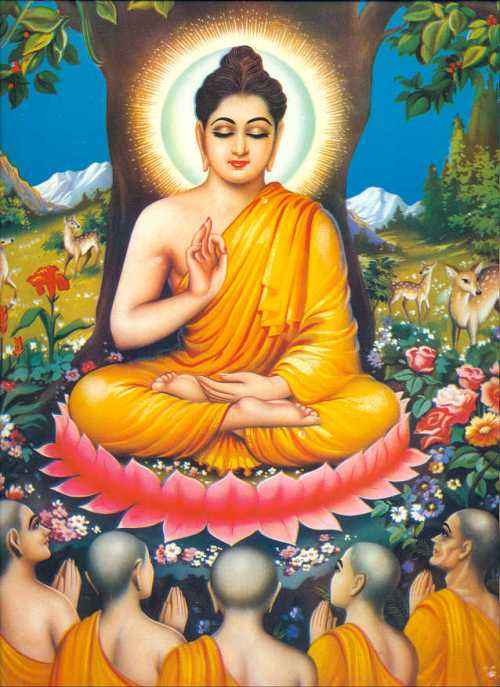

1. Shakyamuni buddha

1. Shakyamuni buddha

Zen originates from the Shakyamuni Buddha's experience, who accomplished awakening in the posture of dhyana (zazen) in India in the 6th century BC. Legend has it that the Buddha showed the assembly of monks a flower, and smiled. Only his disciple Mahakashyapa responded to his smile, so receiving the essence of awakening. This experience "from heart to heart" has then been transmitted from master to disciple, in an uninterrupted line that gave rise to the Zen lineage.

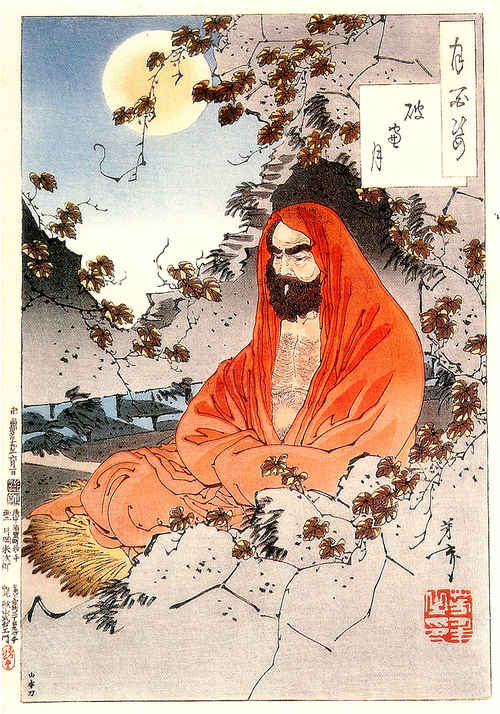

2. Bodhidharma

After spreading for about thousand years in India, this teaching was brought to China by a monk called Bodhidharma in the 5th century AD. According to legend, after visiting a number of temples he came to the Shaolin Temple, where he sat for nine years meditating in a cave. The example of Bodhidharma sitting quiet and motionless facing a wall is still followed today in Zen centres around the world. From then on, Ch' an (Chinese for Zen) enjoyed growing diffusion in China, where it found a fertile ground to further develop.

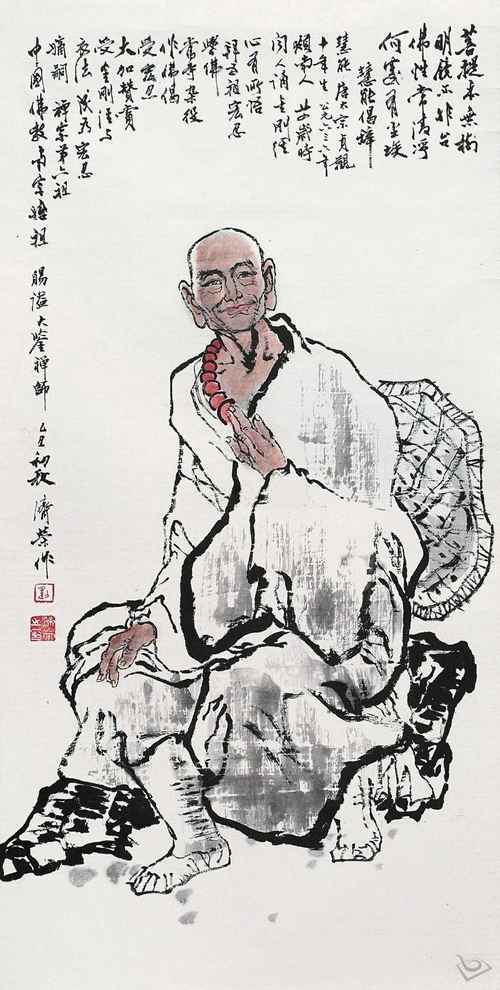

3 sixth Patriarch Hui Neng

Hui-neng (638-713) is possibly the most beloved and respected figure in Zen Buddhism. An illiterate woodcutter, he became the sixth Patriarch of Chinese Zen, and is considered the founder of the "Sudden Awakening School". He is a striking example that neither education nor social background have any influence on achieving enlightenment. The teaching of the Sixth Patriarch emphasizes non-duality and unity of all things.

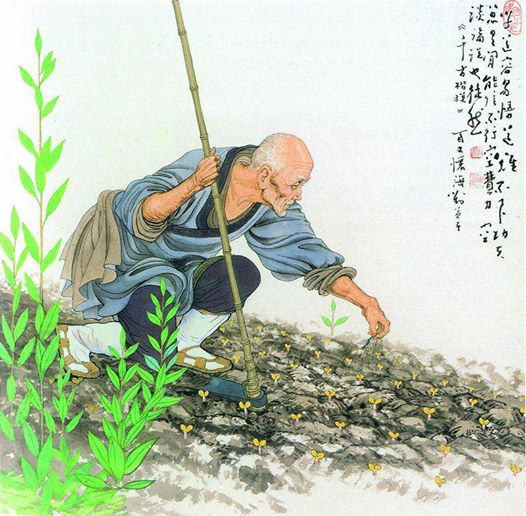

4 the golden age of Ch'an

4 the golden age of Ch'an

In China, it was only with the generation following the Sixth Patriarch that Buddhism flourished and produced its distinctive traits. Especially in this time, Zen established its originality and the purity of its practice through a succession of important masters, such as Masu (709-788), Shitou (ca. 700 - ca. 790), Linchi. (? - 866). Since its appearance, this school built its monasteries in remote places, where surviving was only possible by cultivating land. Thus work became one core factor in practice: "One day without working, one day without eating", said the famous master Pai-chang. Even today, in Zen monasteries all over the world samu (i.e. work) is a crucial element for the spiritual growth of those practising.

5. from china to japan

5. from china to japan

Saichō (767-822), the founder of Tendai Buddhism, introduced the teachings of Chán Buddhism to Japan in the 9th century, but it was during the Kamakura period (12th - 13th centuries) that Japanese Zen defined its own features. Its two major branches, Rinzai (Chinese Lin-chi) and Soto (Chinese Ts'ao-tung), were brought to Japan by the Masters Eisai (1141-1152) and Dogen (1200-1253) respectively.

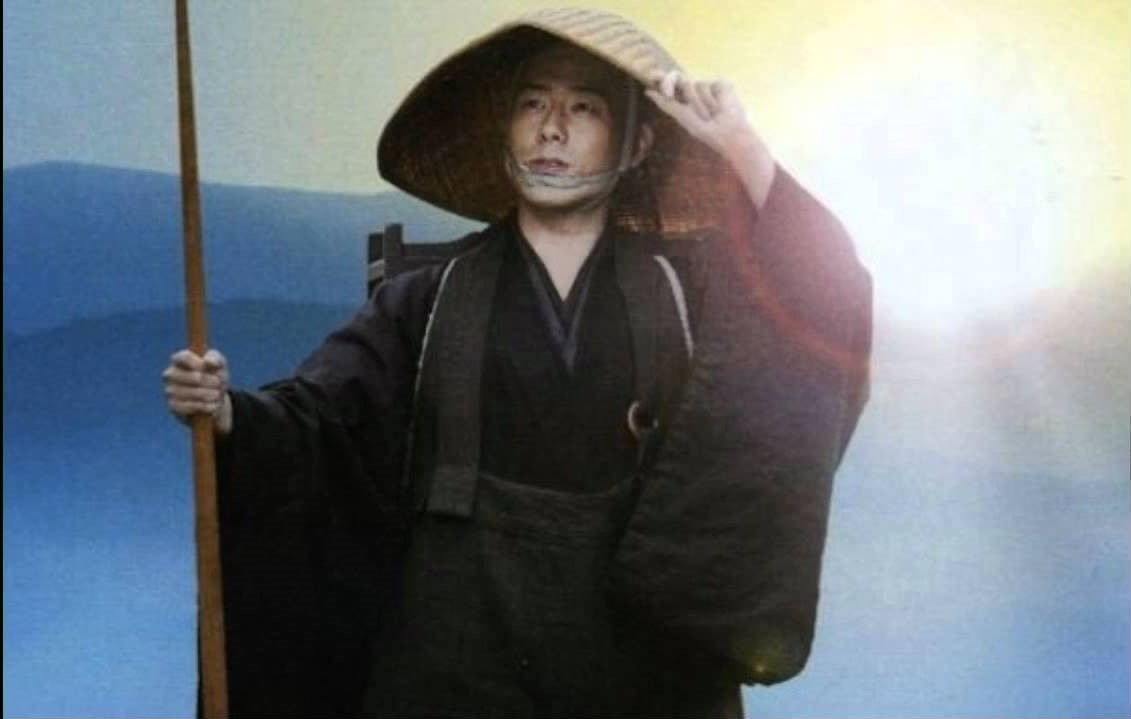

6. Master Dogen

In the 13th century, after a long stay in China, the Japanese monk Dogen introduced Soto Zen in Japan. His major work, Shōbōgenzō (literally "Treasury of the True Dharma Eye"), is among the heights of world religious and philosophical literature. For Dogen, the practice of meditation (Zazen) reveals enlightenment and it is expressed through "letting one's own body-mind drop off", free from the egoic dimension, transcending every dualism.

7. master Keizan

7. master Keizan

After Dogen Zenji, the light of Dharma was transmitted to Ejo Zenji, Gikai Zenji, and later to Keizan Kenji, the fourth ancestor of Japanese Soto Zen lineage. Unlike Dogen Zenji, who had focused on individual and monastic practice, Keizan Zenji used his skills by turning them to the world outside thud spreading the doctrine among the people. Over 15,000 temples bear witness to his efforts today.

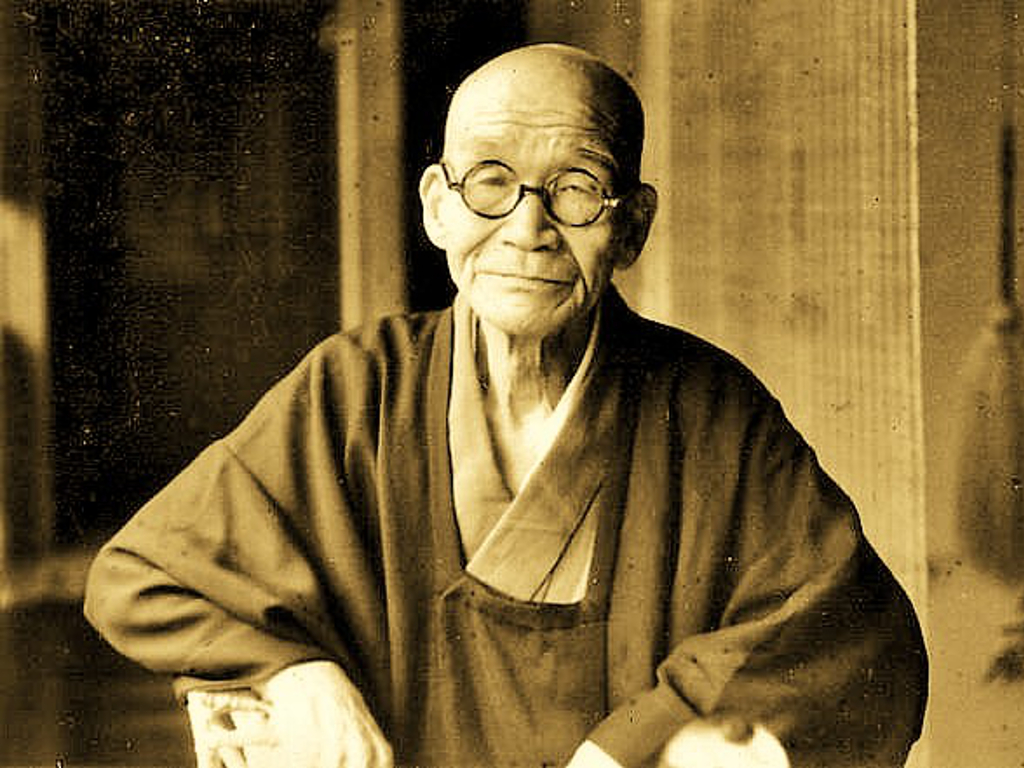

8. Zen in the west

8. Zen in the west

Important masters who have helped spread Zen Soto in the West are: Shunryu Suzuki, Taizan Maezumi, and Daininin Katagiri, who gave this tradition a firm foothold in the United States; Taisen Deshimaru, who spread its practice throughout Europe; and Kosho Uchiyama, successor to Kodo Sawaki, who, though never leaving Japan, strongly influenced many practising in the West.